Although many researchers support the draft, opposition could sink it.

By Emiliano Rodríguez Mega

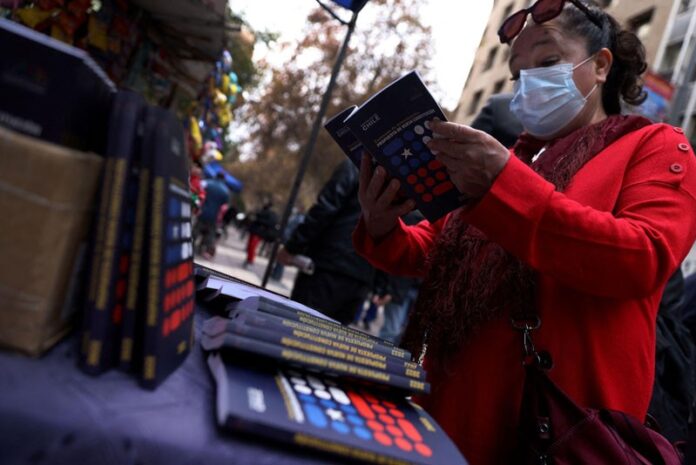

Chile has a new best seller. Since it was finalized on 4 July, a draft of what could become the nation’s constitution has commanded massive numbers of online downloads and crowds waiting to buy paperback copies.

“It may become one of the most-read texts in Chile in recent times,” says Ximena Báez, president of the country’s National Association of Postgraduate Researchers, who is based in Valparaíso.

As researchers in Chile pore over the text, which could reshape their country if approved during a 4 September vote, they are finding a lot to like. It contains a number of articles designed to boost science, expand environmental protection and improve the nation’s education system.

These stand in stark contrast to the contents of the current constitution, enacted more than four decades ago under the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet. That document contains only brief, weak mentions of science, says Santiago-based sociologist José Ortiz Carmona, who authored a 2021 report comparing how science is represented across 193 constitutions — and many see it as the source of profound inequality in Chile.

In October 2019, many Chileans protested decades-long social and economic inequalities stemming, as they saw it, from Pinochet’s policies, and demanded political reform, as well as a new constitution. A year later, the nation voted overwhelmingly to replace the document.

A democratically elected assembly, including scientists, teachers, students and Indigenous representatives, formed to draft it. The product, some have pointed out, is the first constitution in Chile’s history not written by political, economic or military elites.

Despite having been drafted by a diverse group, the vision for Chile’s future has not won favour with everyone. Some academics reject it. And several polls show that the majority of people surveyed plan to vote against it.

Boosting science

Similar to the current constitution, the proposal mandates that the state “stimulate” science and technology — crucial for a country that, for the past decade, has consistently invested less than 0.4% of its gross domestic product in the fields.

But it goes further by adding that scientific achievements and technological solutions should be used to improve the life of Chileans. For example, one of its articles says that the state should rely on science to ensure the “continuous improvement” of public services and goods.

The draft aims to decentralize research. “The largest universities are all in [the capital] Santiago,” Báez says, “so they’re the ones that receive the highest percentage of resources.” The proposed constitution indicates that the state should create the conditions needed to develop science across Chile.

Also included is the state’s obligation to guarantee freedom of research, which, according to Ortiz Carmona, could prevent “undue pressures” from economic or political powers aiming to influence the country’s research. Chile is not immune to such attempts. Last year, for example, presidential candidate José Antonio Kast pledged to banish the Latin American Faculty of Social Sciences, an organization based in San Juan, Costa Rica, that promotes academic research and dialogue, because he considers it “a stronghold of political activism”.

Another big winner in the proposed constitution is education. Beginning in the 1980s, Chile enacted policies supporting privatized education. This resulted in a system that was “deeply unequal, segregated and inefficient”, says Cristián Bellei Carvacho, an education researcher at the University of Chile in Santiago. The new constitution, he says, would reverse that by making education universal, inclusive and free for all.

Environmental protection

The proposal has been called an ‘ecological constitution’ because it emphasizes environmental rights. It says the state has a duty to prevent and adapt to the risks of the climate and biodiversity crises, as well as to mitigate their effects. It “considers that the human being is part of nature, and therefore its care is a condition for human survival”, explains Pilar Moraga, deputy director of the Center for Climate and Resilience Research in Santiago.

Most notably, the document says nature has its own rights, meaning that it can legally be protected, even in the absence of direct harm to people. In an online panel this month, David Boyd, the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights and the environment, who is based on Pender Island, Canada, said that major industries aren’t likely to be pleased with the ecological provisions. If the constitution is enacted, many lawsuits will pop up, he said, and the Chilean government will need to stand its ground to fight against these “vested interests”.

The draft constitution also seeks to protect the rights of Chile’s Indigenous peoples — some 13% of the country’s population — for the first time in its history. The document says research should be ethical and that scientific progress should not be linked to discrimination, which could bolster efforts to rethink the relationship between Chilean scientists and the people they study, says Constanza Silva Gallardo, a substance-use researcher at Pennsylvania State University in University Park, and a member of the Diaguita Mapochogasta Autonomous Community in Santiago. Its inclusion in the draft constitution, she thinks, could make research more participatory, improve informed-consent processes and address the uneven power dynamic between academia and Indigenous groups.

An unclear outcome

Given that initial enthusiasm over the constitution seems to have dissipated, it’s not yet clear what will happen when Chileans vote in September.

Some researchers are unsure about certain aspects of the draft. For example, although the education system is supposed to receive “permanent, direct, relevant and sufficient” funding, research does not seem to get the same consideration, says José Manuel Jiménez, a pharmacologist and secretary of the National Association of Postgraduate Researchers, who is based in Santiago. This could open the door to the government cutting back on science whenever times are tough, he says.

Soledad Bertelsen, a legal researcher at the University of Los Andes in Santiago, worries that the proposed draft lacks any mention of intellectual-property rights, which are guaranteed in the current constitution. It is “an explicit step backwards”, she says, adding that entrepreneurs might decide to move their investments out of Chile.

Still, many scientists are betting on the proposed constitution to take the country into a new age. For Carlos Olavarría, a conservation biologist and director of the Center for Advanced Studies of Arid Zones in La Serena, Chile, the promises to protect the environment and make science a pillar of society point to a future that he is eager to see.

“I don’t know if I will witness it before I die,” he says. “But I dream that Chile walks towards that path.”

Read at Nature.