Authors: Claudia Leal Medina, master’s in sciences on Forests and Environment; Mauro E. González, Mauricio Galleguillos, and Javier Lopatín, CR2 researchers

Edited by: José Barraza, CR2 science disseminator

- Pine trees are highly adapted to fire, effectively reproducing and colonizing native forests after fire events.

- A significant invasion of this exotic species was identified in the remaining native forest fragments following the 2017 wildfire.

- Pine invasion is an emerging pressure due to the positive feedback associated with future fires and the competition it generates with native species in conservation categories.

Pine (Pinus radiata) is a fast-growing tree with high-quality wood. Due to these qualities, the forestry industry has promoted its use in Chile for years. However, it has been demonstrated that the homogeneity of forest plantations of this species facilitates the propagation of fires (McWethy et al., 2018; Bowman et al., 2019).

This last point is of utmost importance since pines are highly adapted to fire, having a mechanism for the rapid establishment of seedlings after a fire (Turner, 2010), while native forests must resprout and re-establish from scarce and dispersed seeds or regrow through vegetative regeneration strategies (Montenegro et al., 2004; Gómez-González & Cavieres, 2009; Keeley, 2012; Gómez-González et al., 2017). Consequently, pines’ rapid regeneration and dispersal exacerbate the threat condition under which native forest patches find themselves after a fire (Kay, 1994; Despain, 2001; Peterken, 2001; Brooker et al., 2008).

To evaluate the impacts of this Pinus radiata invasion on national forest ecosystems damaged by fire, a study used a combination of remote sensing and field data, with the results published in the journal Forest Ecology and Management.

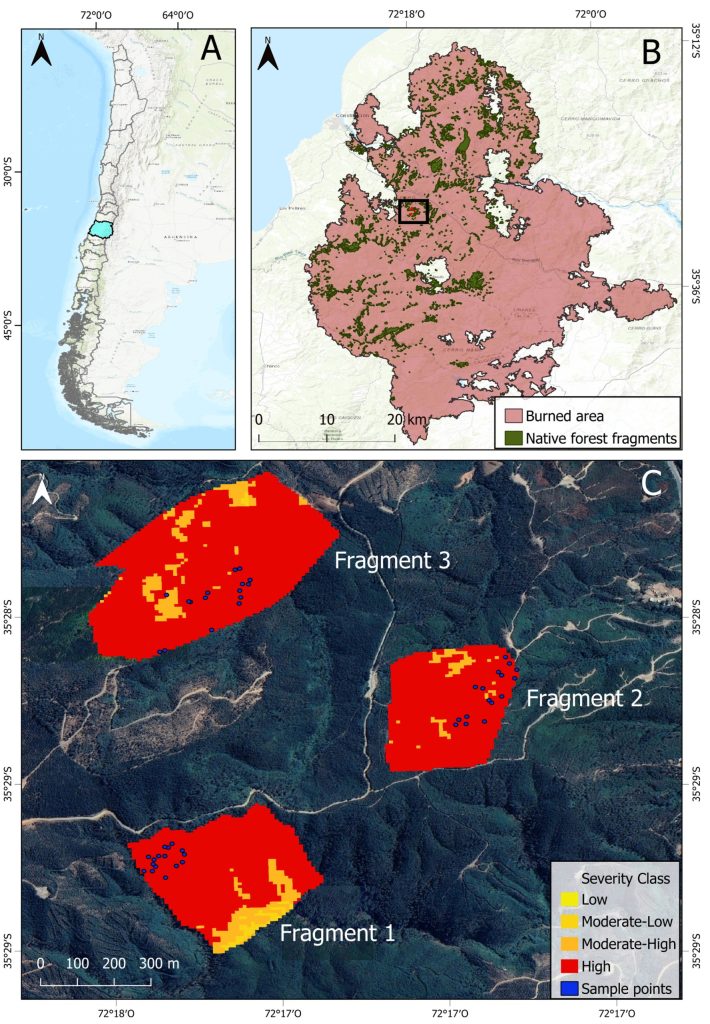

The study area focused on the coastal forest of the Maule region (Figure 1), chosen due to: 1) It is a global biodiversity hotspot with many endemic species, 2) the occurrence of the Las Máquinas wildfire, which burned more than 160,000 hectares in 2017, is the largest in the last fifty years (CONAF, 2017; Lara et al., 2023), and 3. the historical substitution of native forest in this area, initially replaced by agricultural lands and later by forest monocultures, generating deforestation and fragmentation of native forests, leaving only 20% of the original vegetation dispersed in small patches (Bowman et al., 2019).

Figure 1. A. Study region, B. map of the Las Máquinas wildfire (pink) and native forest patches (green), and C. fire severity (from yellow to red) and sampling areas (blue dots).

Figure 1. A. Study region, B. map of the Las Máquinas wildfire (pink) and native forest patches (green), and C. fire severity (from yellow to red) and sampling areas (blue dots).

Results

The abundance of species before the fire was dominated by Hualo (Nothofagus glauca), a native species with 52% presence, followed by other native species such as Peumo (Cryptocarya alba) with 16%, and 27 others with very low representation. However, two years after the fire, both native species presented a relative abundance of barely 5%. In contrast, the most abundant species was pine, with an approximate abundance of 60% and a density that varied between 36,000 and 57,000 individuals per hectare (Figure 2), which far exceeds the density used in commercial plantations.

Figure 2. Pine invasion in a native forest patch following the 2017 wildfire. Image by Claudia Leal.

Figure 2. Pine invasion in a native forest patch following the 2017 wildfire. Image by Claudia Leal.

It should be noted that after the wildfire, a high number of young Pinus radiata individuals coincided with the presence of mature individuals established before the fire. This is due to the historical invasion process caused by land-use changes and landscape fragmentation. The large number of pinecones stored in the canopy of mature pines benefited from the conditions created by the fire, as suggested by other studies (Bustamante & Simonetti, 2005; González et al., 2020; González et al., 2022; San Martín, 2022).

The presence of pines in highly threatened ecosystems negatively impacts the regeneration of native species post-fire, promoting transformations that catalyze the occurrence of new fires (positive feedback) and increasing competition with native species. Although the latter showed a high capacity to resprout after high-magnitude events, the effect of the invasion can significantly alter the natural trajectory and historical dynamics of these forests.

Recommendations

- Conduct early detection of post-fire biological invasions on remaining native forest fragments using remote sensing tools of different spatial resolutions.

- Quantify biological invasions with a combination of methods that include remote and in situ data as critical input for decision-making on management strategies, control, and eradication of invasive species.

- Control and eliminate adult pines established in native forest patches, as they are a source of seed dispersal after fires.

References

CONAF. (2017). Análisis de la Afectación y Severidad de los incendios Forestales ocurridos en enero y febrero de 2017 sobre los usos de suelo y los ecosistemas naturales presentes entre las regiones de Coquimbo y Los Ríos de Chile.

Bowman, D. M., Moreira-Muñoz, A., Kolden, C. A., Chávez, R. O., Muñoz, A. A., Salinas, F., … & Johnston, F. H. (2019). Human–environmental drivers and impacts of the globally extreme 2017 Chilean fires. Ambio, 48, 350-362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-018-1084-1

Brooker, R. W., Maestre, F. T., Callaway, R. M., Lortie, C. L., Cavieres, L. A., Kunstler, G., … & Michalet, R. (2008). Facilitation in plant communities: the past, the present, and the future. Journal of ecology, 18-34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2007.01295.x

Bustamante, R. O., & Simonetti, J. A. (2005). Is Pinus radiata invading the native vegetation in central Chile? Demographic responses in a fragmented forest. Biological Invasions, 7, 243-249.

Despain, D. G. (2001). Dispersal ecology of lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Dougl.) in its native environment as related to Swedish forestry. Forest Ecology and Management, 141(1-2), 59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00489-8

Gómez-González, S., & Cavieres, L. A. (2009). Litter burning does not equally affect seedling emergence of native and alien species of the Mediterranean-type Chilean matorral. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 18(2), 213-221. https://doi.org/10.1071/WF07074

Gómez-González, S., Paula, S., Cavieres, L. A., & Pausas, J. G. (2017). Postfire responses of the woody flora of Central Chile: Insights from a germination experiment. PLOS ONE, 12(7), e0180661. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180661

González, M. E., Sapiains, R., Gómez-González, S., Garreaud, R., Miranda, A., Galleguillos, M., Jacques, M., Pauchard, A., Hoyos, J., & Cordero, L. (2020). Incendios forestales en Chile: Causas, impactos y resiliencia. Centro de Ciencia del Clima y la Resiliencia CR2.

González, M., Galleguillos, M., Lopatin, J., Leal, C., Becerra-Rodas, C., Lara, A., & Martín, J. S. (2022). Surviving in a hostile landscape: Nothofagus alessandrii remnant forests threatened by megafires and exotic pine invasion in the coastal range of central Chile. Oryx, 57(2), 228-238. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605322000102

Kay, M. (1994). Biological control for invasive tree species. New Zealand Forestry, 39(3), 35-37.

Keeley, J. E. (2012). Ecology and evolution of pine life histories. Annals of Forest Science, 69(4), 445-453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-012-0201-8

Lara, A., Urrutia-Jalabert, R., Miranda, A., González, M., & Zamorano-Elgueta, C. (2023). Bosques Nativos. En: Informe País: Estado del medio ambiente y del patrimonio natural 2022 (pp. 3-96).

McWethy, D. B., Pauchard, A., García, R. A., Holz, A., González, M. E., Veblen, T. T., Stahl, J., & Currey, B. (2018). Landscape drivers of recent fire activity (2001-2017) in south-central Chile. PLOS ONE, 13(8), e0201195. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0201195

Montenegro, G., Ginocchio, R., Segura, A., Keely, J. E., & Gómez, M. (2004). Fire regimes and vegetation responses in two Mediterranean-climate regions. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural, 77(3). https://doi.org/10.4067/S0716-078X2004000300005

Peterken, G. F. (2001). Ecological eff ects of introduced tree species in Britain. Forest ecology and management, 141(1-2), 31-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00487-4

San Martín, A. (2022). Los bosques relictos de ruil: Ecología, biodiversidad, conservación y restauración.

Turner, M. G. (2010). Disturbance and landscape dynamics in a changing world. Ecology, 91(10), 2833-2849. https://doi.org/10.1890/10-0097.1